Book Review 1

The Nerine and Amaryllid Society is the fortunate recipient of a copy of a recently published work on the historical background to the introduction of Nerines. Our member, Dr. John David, wrote a review of this publication for the NAAS Journal and, with his permission, the article is reproduced here (with additional photographs).

James Douglas’s A Description of the Guernsey Lilly with a modern commentary and bibliography by Dr Helen Brock

Review by Dr. John David

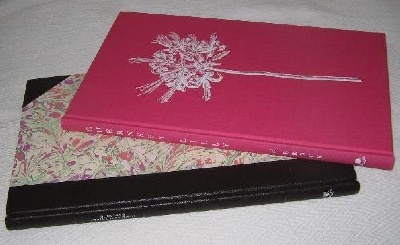

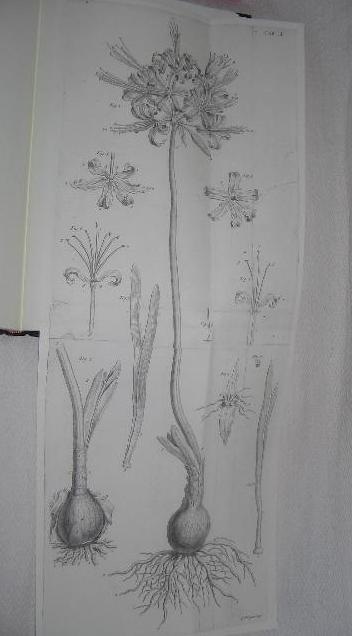

The arrival of Nerine sarniensis in Europe is shrouded in mystery, illuminated by a few facts, but mired in a welter of myth and speculation. We are fortunate that at an early stage the distinguished doctor and Fellow of the Royal Society, James Douglas, published a monograph on the Guernsey Lily (as ‘Guernsay Lilly’ in the 1725 edition) that not only included a botanical description of the plant but also the results of his enquiries in Guernsey as to its occurrence there. This work was first published in 1725, with a second edition in 1729, the latter being reprinted in 1737. The first edition appeared some 90 years after the first definite report of N. sarniensis in Europe, and therefore is important as a record of what was known at a time much closer to when the plant was introduced than our own. The present publication comprises two volumes: one being a facsimile reproduction of the 1737 reprint of the second edition, the other being a recent memoir written by Dr Helen Brock in the early 1990s. I will not discuss the facsimile of the Douglas monograph in this review, as it does not require further comment. While 185 copies of the facsimile and commentary were printed at the time, the work was never published, and was rescued by the present publisher some 20 years later. Those who attended this year’s NAAS AGM will have been able to admire the beautiful presentation of the volumes. The facsimile is half bound in dark (described by the publisher as ‘chocolate’) leather, with leather corners front and back and subtle blind tooling on the leather, and bands on the spine to give an eighteenth century feel. The binding is completed by marbled paper in pink and cream with speckles of gold. The quality of the binding is evident from the way the book remains open at each page. The Commentary is a modern binding covered in a vibrant pink cloth reminiscent of the flowers of Nerine, with a Nerine embossed in white on the front. Printed on almost foolscap sized paper, both volumes are rather slim, the first being 80 pages with three fold-out illustrations as in the original, the second is 88 pages, with 18 pages of introduction to the facsimile. The volumes are contained in a cloth-covered slipcase also, according to the publisher in chocolate.

As noted above, the principal interest of Douglas’s monograph is his investigations into the original introduction of N. sarniensis into Europe. This account is given in pages 10 – 19 of the facsimile. It was Robert Morison, Professor of Botany at Oxford who, in 1680, recorded the story of the Nerine “roots” being cast ashore following the stranding (or shipwreck) of a boat carrying the plant from Japan. In Morison’s and Douglas’s time, both of which pre-date Linnaeus’s ordering of plant nomenclature in 1753, the Guernsey lily was generally known as Lilio-Narcissus or Narcissus. Indeed when Jacob Cornut first described the plant in 1735 he named it Narcissus japonicus. Linnaeus, however, named it Amaryllis sarniensis, taking the species name from Douglas’s earlier name of Lilio-Narcissus Sarniensis Autumno florens[1]. It was not until Herbert in 1820 that the generic name Nerine was introduced for it. Herbert, drawing on the poetry of the renaissance, and being aware of the myth first reported by Morison, chose the name to allude to the sea nymph that rescued Vasco da Gama’s ship in Camoens’s epic poem, Os Lusiades. Dr Brock was unaware of this and chose in her introduction to reiterate the widely held view that the name is derived from Greek mythology, but compounds the error by suggesting the word nerine is Greek, when no such word is to be found in any Greek dictionary. Brock’s Commentary echoes Douglas’s monograph in taking the five chapter headings from it. Each chapter provides additional information and context for understanding Douglas’s account. Some of this is supported from Brock’s study of Douglas’s papers which are held in the Hunterian Museum in Glasgow. However, while she was obviously a diligent researcher and has brought together much useful information there are a number of errors, mainly taxonomic, that the reader should be aware of[2]. This is particularly evident in Appendix 6, where the author has updated Douglas’s original list of synonyms and added further names from the account by Traub (1967). Notwithstanding this, the author does uncover some useful additional information about the early cultivation of N. sarniensis from contemporaneous literature. The Commentary includes, in addition, James Knowlton’s account of his visit to Guernsey on Douglas’s behalf to enquire into the origin of the Guernsey lily. This is followed by seven Appendixes, four of which are poems relating to the lily and the final Appendix is a facsimile of the first few pages of the 1729 edition where they vary from the 1737 reprint. There are notes and references at the end, but no index.

[1] In the 1725 Edition Douglas gives it the name Narcisso-Lirion Sarniense but in the second edition fell into line with the nomenclature then current on the continent for this group of plants. In both editions he also cites the name ‘Lilium Sarniense’ to which he adds “vulgo”, meaning that this is its common name, i.e. the Guernsey lily. This should not be taken to be a botanical name.

[2] These are given in an erratum list supplied with the Commentary. The list does not cover the errors in Appendix 6, which are too technical to be of use to the general reader.

Perhaps the most important element of Dr Brock’s Commentary is her analysis of the conflicting accounts of how the Guernsey lily came to Guernsey. The shipwreck story, published by Morison was apparently derived from one of his students who was the second son of Lord Hatton, Governor of the Channel Islands after the Restoration in 1660. While it was also said that the first roots had been presented to an inhabitant of Guernsey by a grateful stranded sailor, this version of events rarely seems to have received much exposure in later accounts – perhaps lacking the romance of the shipwreck version. Douglas opted for a combination of the two stories. Brock brings into this the complicating factor of the Commonwealth soldier, General Lambert, who was imprisoned on the island during Lord Hatton’s governorship, and whose daughter married Morison’s student, Charles Hatton. We know that Lambert had at least one plant of Nerine sarniensis while he was living at Wimbledon during the Commonwealth, since there is a painting of it in Marshall’s Florilegium, now held in the Library at Windsor Castle. The painting, reproduced as the frontispiece to Brock’s Commentary, dates from 1659, just 25 years after it was first described from a plant grown by the Paris nurseryman Jean Morin. This then leads to two further explanations: first, that Lambert received the nerine from the loyal parliamentarians of Guernsey and second, that Lambert brought the bulbs to the island and is the source of their introduction. Such evidence as is available rules the second explanation although the first remains possible, in that Lambert could have obtained his plants either from Guernsey or from Paris.

To lay to rest the shipwreck story Brock has examined the shipping records held by both the Dutch and English at the time and established that no ship was lost on the Guernsey coastline. This seems finally to nail what was always an inherently improbable tale, but one which clearly captures the popular imagination as she points out in relation to the Scarborough lily (Cyrtanthus elatus) which has a definite date and route of introduction, but is said likewise to have arrived as the result of a shipwreck. Not content with disproving the story, Brock goes on to explore how the story came about. Her hypothesis is that the dangerous post-Restoration politics and the Catholic conspiracies with which both Charles Hatton and General Lambert were innocently involved, led to Hatton asking his mentor, Morison, to cover up the true explanation for the source of the bulbs by giving the shipwreck story in his book. Although not impossible, since it is not known for definite how the bulbs reached Guernsey (or even how they reached Paris), this elaborate saga seems rather unnecessary.

It is intriguing, though, that by Douglas’s time, if not before, Guernsey was exporting the bulbs to England in significant numbers. This would suggest that someone had quickly spotted the potential of Nerine and had managed to bulk them up in sufficient numbers to support the trade. This, at a time when cultivation under glass would have been rare or nonexistent: the earliest greenhouse on Guernsey still in existence dates back to 1792. It is also widely held on Guernsey that the original nerines continue to be grown and flower outside at the foot of a sheltered house wall. This too is referred to by Brock, but since then it has been found that these nerines closely resemble those growing on Table Mountain. Thus it should not be doubted that the plant arrived on Guernsey sometime in the first half of the seventeenth century: whether it was then transmitted to Paris, or arrived at Paris independently it does not now seem possible to determine. While the earliest explorations date from the early 1500s and by 1600 a number of South African plants had been brought back to Europe, it was not until 1652 that the Dutch established an outpost at the Cape of Good Hope. It is curious that, given their horticultural tradition they did not bring back the bulb themselves. Indeed in Douglas’s monograph he states that the Dutch received it through a student from Guernsey studying at Leiden during the time when Dr Hotton (Petrus Houttuyn, 1648-1709) was Professor of Botany there.

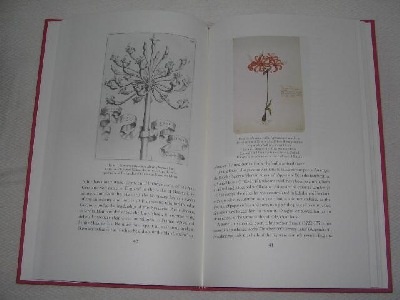

The mystery of the introduction of N. sarniensis to Europe has baffled all those that have studied the evidence available at the time. In her Commentary Brock has brought to light further information, mainly from unpublished sources, which does make a further step in our understanding of the problem. She add some fascinating information from her research, and provides a useful survey of the literature, as well as illustrations of the time, including some hitherto unseen paintings such as the one acquired by William Sherard, now held at the Botany School at Oxford, thankfully reproduced in colour.

Without doubt we should be grateful to the publishers for being willing to give this work a wider circulation and admire their courage in producing such a fine edition. At £375, given the quality of the binding and presentation and the limited number of copies, the book is realistically priced. This is no consolation to many Nerine enthusiasts for whom the price puts the book well beyond their means, while undoubtedly it will appeal to the deeper-pocketed denizens of the Channel Islands. However, I understand the publishers are generously donating a copy to the Nerine & Amaryllid Society and I encourage those unable to afford this work, to consult the Society’s copy.

For more information about books held by NAAS , please click here.